Court reporters must “write” (stroke) between 225 and 280 words a minute on a court reporting machine in order to become certified by the state in which they practice or to receive a nationally recognized certification by the National Court Reporters Association.

Although each state has its own certification criteria, most of them mirror the criteria established by the National Court Reporters Association. There is a lot of discussion among court reporters these days about the lawyers and witnesses speaking faster and faster. So how do reporters get it all down? Many aspiring court reporters find that participating in court reporter mentorship programs available can significantly enhance their skills and confidence. These programs often provide invaluable tips and techniques from experienced professionals in the field. As a result, mentees are better prepared to meet the growing demands of their profession.

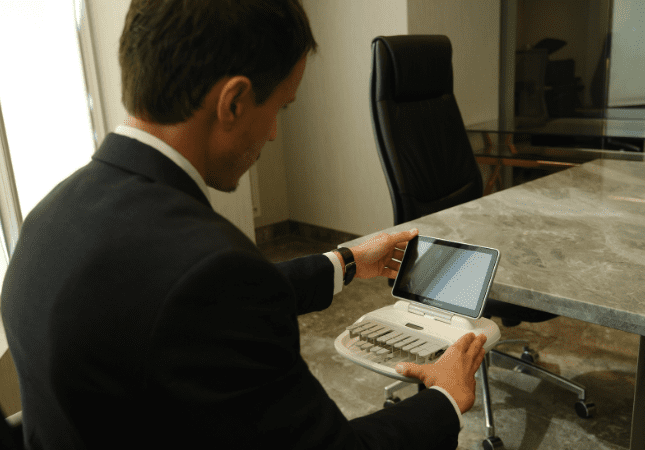

Stenographic court reporters are taught machine shorthand; that is, they learn how to write on a stenotype machine, which is a uniquely designed machine with keys representing certain letters of the alphabet. You might be surprised to learn that not all letters of the alphabet are represented by a key on the machine; the reporter must press down two or more keys simultaneously to represent those letters or “sounds.” The best way to understand how the stenotype machine works is to compare it to a piano. If one key is depressed, you have a note; if multiple keys are depressed, you have a chord.

Learning to write on a stenotype machine is like learning an entirely new “language” and alphabet. Court reporters write what they hear phonetically, depressing multiple keys simultaneously to represent the sounds, syllables or words they hear. The stenotype machine is connected to a laptop computer which contains a steno-English “dictionary,” which is software customized by the court reporter to their writing “theory.” It should be noted that a court reporter’s writing is individually unique.

No two reporters write exactly alike. Words that are not in the court reporter’s dictionary will be translated phonetically or will appear in stenotype language on the court reporter’s laptop or the attorneys’ laptops receiving the realtime feed from the court reporter.

The stenotype keyboard is divided into four distinct areas: The number bar located across the top of the keyboard; the left and right side of the machine, each with an upper and lower bank; and the vowels, which are located at the bottom center of the machine. The left side of the machine, upper and lower banks, represent the consonants used to begin words or syllables; and the right side of the machine, upper and lower banks, represent the consonants used at the end of words or syllables. Left fingers are placed in the middle of the two banks on the left; right fingers are placed in the middle of the two banks on the right, and each thumb controls two vowels on either side.

A court reporter will depress a combination of keys on the left and/or right side of the machine in order to create the sound of a single consonant. As with the consonants, the court reporter will also depress a combination of vowel keys to represent different sounds, such as long and short vowels. Due to the intricacies of the machine and the skill itself, if a reporter misses even a single key or depresses an incorrect key, an entirely different consonant or vowel may be translated by the dictionary, resulting in an incorrect “translation” of the intended word. To illustrate how this works, the word “world” is written by depressing the W-O-R-L-D keys simultaneously, with the left ring finger depressing the W key; the left thumb depressing the O key, the right index finger depressing the R key; the right ring finger depressing the L key and the right pinky finger depressing the D key. The three-letter word “net” is a bit more complicated, since there is no N represented on the left side of the keyboard. N on the left side of the keyboard is represented by simultaneously depressing the T-P-H letter combination. Therefore, in order to write the word “net,” the reporter must depress the following keys at the same time: T-P-H-E-T. If the reporter doesn’t press down hard enough on the initial T, or if the reporter does not depress the T key at all, or if the reporter depresses the S key instead, it will cause a mistranslate (wrong word) or an untranslate (no dictionary match). For example, “met” instead of “net” or S-P-H-E-T will appear on the realtime feed since the dictionary will likely be unable to translate the word into English.

To complicate matters further, the reporter must hear and understand the word and depress the correct keys within a split second (or less) of hearing it. It’s a sort of mental gymnastics that the reporter must do with every word spoken – hearing, understanding, writing, and anticipating the translation. Court reporters cannot become Certified Realtime Reporters (CRRs) unless their translation rate meets a minimum 96 percent accuracy rate for a 5-minute dictation. Certified Realtime Reporters have achieved this level of expertise through nothing short of perfecting their writing and refining their software.

Court reporters must also have exemplary English skills, an expansive vocabulary, a strong work ethic, and the ability to focus for hours on end. Court reporters serve a vital role in the judicial process. In fact, the State of Wisconsin dedicates an entire week to appreciating its court reporters. The journey to becoming a court reporter involves rigorous training and dedication. Aspiring individuals often enroll in specialized programs that equip them with the necessary skills and knowledge to excel in this crucial profession. Moreover, hands-on experience through internships provides invaluable insight into the daily responsibilities and challenges faced by court reporters. As court reporters seek to expand their careers, they may explore various court reporting opportunities in Florida. The state’s growing legal sector presents a wealth of job openings, appealing to those ready to embark on this rewarding path. Networking with established professionals and joining local organizations can further enhance their chances of success in this dynamic field.

Planet Depos would like to take this opportunity to thank its court reporters for their ongoing commitment to improving their skills and providing accurate verbatim transcripts for our valued clients.