Significant Points

- Job prospects remain strong, especially for those with advanced certifications and realtime skills.

- Demand for broadcast captioning, Communication Access Realtime Translation (CART), and digital court reporting continue to grow due to accessibility needs and technology adoption.

- Training length and licensure requirements vary by technology and state.

Nature of the Work

Court reporters create accurate, verbatim transcripts of legal proceedings, meetings, and other events where a precise written record is required. They play a vital role in preserving the official record for courts, attorneys, government bodies, and private organizations. As advancements in automation and artificial intelligence continue to emerge, future technologies in court reporting hold the promise of enhancing the speed and accuracy of transcript production. Innovations such as real-time speech recognition and advanced software tools may revolutionize the way court reporters work, allowing them to focus more on the substantive aspects of legal proceedings. Adopting these technologies will not only improve efficiency but also ensure a more accessible judicial process for everyone involved.

Beyond the courtroom, court reporters:

- Provide CART services to students and professionals who are deaf or hard of hearing.

- Caption live television, webinars, and streamed content for accessibility.

- Create verbatim transcripts of legal proceedings such as depositions, meetings, hearings, and other events.

- Support virtual legal proceedings in an increasingly remote-friendly judicial system.

Methods of Court Reporting

- Stenographic: Reporters use stenotype machines, with backup digital audio recording devices, to transcribe at speeds exceeding 225 wpm, either for later transcription or for immediate display in person on monitors or streaming to remote locations using specialized realtime software that integrates automatic speech recognition and other technologies to improve accuracy.

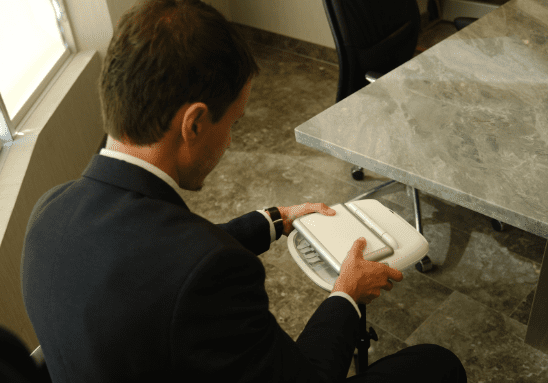

- Digital: Reporters use state-of-the-art audio recording equipment with redundancies to capture proceedings, either for later transcription or for immediate display in person on monitors or streaming to remote locations using speech recognition software.

- Voice: Reporters repeat testimony into a voice silencer mask, with backup digital audio recording devices, either for later transcription or for immediate display in person on monitors or streaming to remote locations using speech recognition software and other technologies to improve accuracy.

Additional Duties

- Provide accurate and on-time transcripts of proceedings. Most experienced court reporters of all methods engage the services of scopists (editors) and proofreaders to ensure the accuracy, efficiency and quality of final transcripts.

- Maintain hardware and software to current industry standards.

- Manage secure digital storage and retrieval of transcripts.

- Provide realtime feeds and immediate post-event transcripts for legal, broadcast, or educational use.

Work Environment

- Many court reporters now work in hybrid settings: courts, corporate offices, or home-based offices.

- Remote work is increasingly common for freelancers, CART providers, captioners, and even some official courtroom reporters.

- The job can involve long periods of sitting and concentration, posing risks of repetitive stress injuries.

- Deadlines and accuracy requirements can add stress, especially in high-profile legal cases or live captioning of emergencies.

Training, Licensure, and Certification

Training

- Stenographic reporters: Typically require 2–4 years of training to achieve speeds of 225+ wpm with accuracy. There is a high dropout rate associated with stenographic training.

- Digital reporters: Complete training programs lasting several months, including extensive hands-on experience.

- Voice reporters: Can achieve entry-level proficiency within a year; realtime proficiency takes longer.

There are 18 schools nationwide that offer National Court Reporters Association (NCRA)-approved stenographic programs, both in-person and online. These programs prepare students for various career paths, including court reporting job opportunities in California. With the increasing demand for certified court reporters, graduates can find diverse roles in legal settings, ensuring their skills are put to practical use. The flexibility of these programs also allows students to pursue job openings in different regions as they complete their training. new court reporters often seek advice on their first court reporting assignment tips to help them navigate the demands of the job. Building strong relationships with attorneys and other legal professionals can also enhance their experience and provide valuable networking opportunities. By honing their skills and adapting to different courtroom environments, they can set themselves up for a successful career.

Licensure and Certification

- Requirements vary by state. Many states require Certified Shorthand Reporter (CSR) or notary public status.

- Key certifications:

- NCRA: Registered Professional Reporter (RPR), Registered Merit Reporter (RMR), Registered Diplomate Reporter (RDR), Certified Realtime Reporter (CRR), Certified Realtime Captioner (CRC)

- NVRA: Certified Verbatim Reporter (CVR), Realtime Verbatim Reporter (RVR).

- AAERT: Certified Electronic Reporter (CER), Certified Electronic Transcriber (CET), Certified Deposition Reporter (CDR)

Certification is highly valued and often required by employers.

Employment and Outlook

- 2024 employment: ~17.500 jobs in 2023 in the U.S. – court reporters and captioners (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics).

- Projected growth: ~2% from 2023-2033, yielding around 300 new positions annually, primarily to replace retirees (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics).

- Outlook: U.S. court reporters and captioners enjoy relatively stable employment with modest growth and solid pay. Growing shortages and regulatory demand ensure ongoing opportunities – particularly for those with specialized skills – while AI tools increasingly augment, but do not replace, human stenographers.

Earnings

- Median annual salary (2024): $68,000 (U.S. BLS)

- Range: $40,000 (entry-level reporters) to $300,000+ (experienced realtime court reporters in large markets).

- Freelance reporters earn per-page, per-job, or hourly rates, with wide variability based on location and specialization. Freelance reporters typically enjoy greater flexibility than their employee counterparts.

- Official court reporters, captioners, and digital reporters are typically employees who receive full benefits, along with paid equipment. Captioners and digital reporters may also receive full or partial training. In contrast, freelance reporters and CART providers are usually independent contractors who must cover their own expenses.

The Future of Court Reporting

Court reporting is evolving in response to:

- Technology: expanded use of AI-assisted transcription tools, though human reporters remain essential for accuracy and certification.

- Labor shortages: according to the NCRA, thousands of stenographers are expected to retire within the next 5-10 years; the pipeline of new talent isn’t replacing them fast enough.

- Legal demand: growing remote and hybrid proceedings in courts and arbitration.

- Accessibility needs: rising demand for accessibility services (CART, captioning) driven by legal mandates)

Key Trends Shaping the Future

- Persistent Demand, Especially in Litigation

- Legal proceedings still require an accurate, realtime record. Despite technological changes, courts and law firms rely on human oversight for accuracy.

- Retirement of veteran stenographers (many trained in the 1980s and 1990s) is creating a supply shortage, particularly in high-volume litigation states like California, Texas, and New York.

- This shortage is driving up demand – and often pay – for qualified professionals.

- Growth in Captioning and CART Services

- There’s a rising need for accessibility across education, live events, media, and business meetings.

- CART (Communication Access Realtime Translation) providers are in growing demand, especially with ADA requirements and increased virtual engagement.

- Realtime captioning is now standard in many industries – not just a bonus.

- Hybrid Roles and Expanded Opportunities

- The field is diversifying beyond just courtrooms:

- Remote depositions

- Educational accessibility

- Broadcast captioning

- Government and corporate transcription

Many reporters now work hybrid schedules or across specialties.

Technology’s Impact: AI and Court Reporting

Opportunities

- Stenographers and voice reporters who maximize the use of artificial intelligence can work more efficiently, take on more work, and increase their income by leveraging technology and smarter workflows.

AI software can instantly translate steno or voice input into text, allowing for quicker rough drafts.

In Summary

Court reporting has a strong future – but a different one:

- Hybrid roles, not just courtroom work

- Complementary technology, not full replacement

- More remote work and accessibility services

- High demand due to a shrinking supply of trained professionals

Those entering the field now – especially with certifications – are likely to find stable, well-paying, and diverse opportunities. As the demand for skilled professionals continues to rise, there are numerous career opportunities in court reporting that offer both flexibility and growth. This profession not only allows individuals to work in various settings, from legal environments to freelance work, but also provides a chance to contribute to the judicial process. With technology advancing, there are exciting paths available, such as real-time reporting and transcription services, making it an ideal time to pursue this career.